- Posts: 119

- Thank you received: 104

Special Operations

- Doc

-

Topic Author

Topic Author

- Offline

- Good day!

Less

More

5 years 5 months ago - 4 years 7 months ago #1

by Doc

Special Operations Executive (SOE) had been set up in 1940 to coordinate and carry out subversive action against German forces in occupied countries, including France. SOE sent agents to support resistance groups and provided them with weapons, sabotage materials and other supplies.

There was only limited cooperation between SOE and those planning Operation ‘Overlord’, and the exact role resistance forces would have during the invasion was not decided until the week before D-Day. There were also differences between the many groups that made up French resistance – each had different origins, methods and political aims – as well as rivalries between the various intelligence organisations, including SOE. This made it difficult to effectively coordinate their activities.

Secret messages were broadcast on the eve of D-Day alerting SOE agents and resistance forces to make ‘maximum effort’ in carrying out acts of sabotage. Earlier messages warning of the impending invasion had been broadcast on 1 May and 1 June. These were picked up by the Nazi Security Services and reported to the High Command. But these warnings were not acted upon and therefore did not endanger the landings by giving away the element of surprise.

On and shortly after D-Day, three-man special forces ‘Jedburgh’ teams made up of British, American and French personnel in uniform were dropped into France to align French resistance activities with Allied strategy. They also helped to undermine German defences in Normandy by disabling rail, communication and power networks in the invasion area. This disruption helped prevent the Germans from concentrating their strength in Normandy on D-Day and in the weeks that followed.

Special Operations was created by Doc

Special Operations Executive (SOE) had been set up in 1940 to coordinate and carry out subversive action against German forces in occupied countries, including France. SOE sent agents to support resistance groups and provided them with weapons, sabotage materials and other supplies.

There was only limited cooperation between SOE and those planning Operation ‘Overlord’, and the exact role resistance forces would have during the invasion was not decided until the week before D-Day. There were also differences between the many groups that made up French resistance – each had different origins, methods and political aims – as well as rivalries between the various intelligence organisations, including SOE. This made it difficult to effectively coordinate their activities.

Secret messages were broadcast on the eve of D-Day alerting SOE agents and resistance forces to make ‘maximum effort’ in carrying out acts of sabotage. Earlier messages warning of the impending invasion had been broadcast on 1 May and 1 June. These were picked up by the Nazi Security Services and reported to the High Command. But these warnings were not acted upon and therefore did not endanger the landings by giving away the element of surprise.

On and shortly after D-Day, three-man special forces ‘Jedburgh’ teams made up of British, American and French personnel in uniform were dropped into France to align French resistance activities with Allied strategy. They also helped to undermine German defences in Normandy by disabling rail, communication and power networks in the invasion area. This disruption helped prevent the Germans from concentrating their strength in Normandy on D-Day and in the weeks that followed.

Last edit: 4 years 7 months ago by snowman. Reason: Video deleted

The following user(s) said Thank You: Maki, WANGER, p.jakub88

Please Log in or Create an account to join the conversation.

- Doc

-

Topic Author

Topic Author

- Offline

- Good day!

Less

More

- Posts: 119

- Thank you received: 104

5 years 4 months ago - 5 years 4 months ago #2

by Doc

The Force 136 was the general cover name, from March 1944, for a Far East branch of the British World War II intelligence organisation, the Special Operations Executive (SOE). Originally set up in 1941 as the India Mission with the cover name of GSI(k), it absorbed what was left of SOE's Oriental Mission in April 1942. The man in overall charge for the duration of the war was Colin Mackenzie.

The organisation was established to encourage and supply indigenous resistance movements in enemy-occupied territory, and occasionally mount clandestine sabotage operations. Force 136 operated in the regions of the South-East Asian Theatre of World War II which were occupied by Japan from 1941 to 1945: Burma, Malaya, China, Sumatra, Siam, and French Indo-China (FIC).

Although the top command of Force 136 were British officers and civilians, most of those it trained and employed as agents were indigenous to the regions in which they operated. Burmese, Indians and Chinese were trained as agents for missions in Burma, for example. British and other European officers and NCOs went behind the lines to train resistance movements. Former colonial officials and men who had worked in these countries for various companies knew the local languages, the peoples and the land and so became invaluable to SOE. Most famous amongst these officers are Freddie Spencer Chapman in Malaya and Hugh Seagrim in Burma.

Replied by Doc on topic Special Operations

Force 136

The Force 136 was the general cover name, from March 1944, for a Far East branch of the British World War II intelligence organisation, the Special Operations Executive (SOE). Originally set up in 1941 as the India Mission with the cover name of GSI(k), it absorbed what was left of SOE's Oriental Mission in April 1942. The man in overall charge for the duration of the war was Colin Mackenzie.

The organisation was established to encourage and supply indigenous resistance movements in enemy-occupied territory, and occasionally mount clandestine sabotage operations. Force 136 operated in the regions of the South-East Asian Theatre of World War II which were occupied by Japan from 1941 to 1945: Burma, Malaya, China, Sumatra, Siam, and French Indo-China (FIC).

Although the top command of Force 136 were British officers and civilians, most of those it trained and employed as agents were indigenous to the regions in which they operated. Burmese, Indians and Chinese were trained as agents for missions in Burma, for example. British and other European officers and NCOs went behind the lines to train resistance movements. Former colonial officials and men who had worked in these countries for various companies knew the local languages, the peoples and the land and so became invaluable to SOE. Most famous amongst these officers are Freddie Spencer Chapman in Malaya and Hugh Seagrim in Burma.

Last edit: 5 years 4 months ago by Doc.

The following user(s) said Thank You: Rs_Funzo, Maki, p.jakub88

Please Log in or Create an account to join the conversation.

- snowman

-

- Offline

- Your most dear friend.

5 years 4 months ago - 5 years 4 months ago #3

by snowman

Operation Biting was a daring Combined Operations raid on a German radar station at Bruneval in northern France.

In February 1942, men of the newly formed British 1st Airborne Division went into action for the first time. Their target was the German 'Wurzburg' radar installation at Bruneval. Their objective was to seize vital radar components and to bring them back to the UK for inspection by trained scientists.

Radar was one of the key, high-technology battlegrounds of the war. Without radar, the outcome of RAF Fighter Command's narrow victory in the "Battle of Britain", might have been very different. The Luftwaffe, meantime, were using radio navigation aids for blind bombing during the blitz. In 1941, Bomber Command extended its reach into the German heartland, forcing the Luftwaffe to develop its own defensive radars and Britain responded with jamming techniques. So the "battle of the beams" developed between scientists on both sides as they strived to gain the advantage. Heading up the British team, was Dr RV Jones, of the Air Staff.

From intelligence gathered by the French resistance, a frontal assault on the beach would suffer heavy casualties from enemy defensive positions. It was, therefore, decided to drop paratroops inland by Whitley bombers under the command of Squadron Leader Charles Pickard. The plan envisaged the raiding party being recovered from the beach by the Royal Navy, with No 12 Commando providing covering fire against German coastal positions.

C Company of the 2nd Battalion of the 1st Parachute Brigade was chosen for the operation - 120 men commanded by Major John Frost. Nearly all the men were drawn from Scottish regiments, including the Black Watch, Cameron Highlanders, King's Own Scottish Borderers and the Seaforths. To identify the components of interest, they were to be accompanied by RAF radar operator, Flight Sergeant CWH Cox. He was a former cinema projectionist, ill equipped for such an operation since he had never been in a ship, or on an aircraft, before!

The utmost secrecy was applied to the project from the outset. If German Intelligence became aware of British interest in the Bruneval site, the whole project would be compromised with disastrous consequences for those taking part. The "need to know" doctrine was, therefore, strictly applied. The parachute unit, for example, believed the War Cabinet wanted them to demonstrate techniques and capabilities for raiding a headquarters building behind enemy lines.

The plan for the operation was simple. The paratroops were to be dropped in three units. The first, under the leadership of Lieutenant John Ross and Lieutenant Euen Charteris, was to advance on, and capture, the beach. The second, subdivided into three sections and commanded by Frost, was to seize a nearby villa and the Wurzburg, while the third, led by Lieutenant John Timothy, was to act as a rearguard and reserve ...

"Straight and narrow is the path."

Replied by snowman on topic Special Operations

Operation Biting aka The Bruneval Raid

Operation Biting was a daring Combined Operations raid on a German radar station at Bruneval in northern France.

In February 1942, men of the newly formed British 1st Airborne Division went into action for the first time. Their target was the German 'Wurzburg' radar installation at Bruneval. Their objective was to seize vital radar components and to bring them back to the UK for inspection by trained scientists.

Radar was one of the key, high-technology battlegrounds of the war. Without radar, the outcome of RAF Fighter Command's narrow victory in the "Battle of Britain", might have been very different. The Luftwaffe, meantime, were using radio navigation aids for blind bombing during the blitz. In 1941, Bomber Command extended its reach into the German heartland, forcing the Luftwaffe to develop its own defensive radars and Britain responded with jamming techniques. So the "battle of the beams" developed between scientists on both sides as they strived to gain the advantage. Heading up the British team, was Dr RV Jones, of the Air Staff.

From intelligence gathered by the French resistance, a frontal assault on the beach would suffer heavy casualties from enemy defensive positions. It was, therefore, decided to drop paratroops inland by Whitley bombers under the command of Squadron Leader Charles Pickard. The plan envisaged the raiding party being recovered from the beach by the Royal Navy, with No 12 Commando providing covering fire against German coastal positions.

C Company of the 2nd Battalion of the 1st Parachute Brigade was chosen for the operation - 120 men commanded by Major John Frost. Nearly all the men were drawn from Scottish regiments, including the Black Watch, Cameron Highlanders, King's Own Scottish Borderers and the Seaforths. To identify the components of interest, they were to be accompanied by RAF radar operator, Flight Sergeant CWH Cox. He was a former cinema projectionist, ill equipped for such an operation since he had never been in a ship, or on an aircraft, before!

The utmost secrecy was applied to the project from the outset. If German Intelligence became aware of British interest in the Bruneval site, the whole project would be compromised with disastrous consequences for those taking part. The "need to know" doctrine was, therefore, strictly applied. The parachute unit, for example, believed the War Cabinet wanted them to demonstrate techniques and capabilities for raiding a headquarters building behind enemy lines.

The plan for the operation was simple. The paratroops were to be dropped in three units. The first, under the leadership of Lieutenant John Ross and Lieutenant Euen Charteris, was to advance on, and capture, the beach. The second, subdivided into three sections and commanded by Frost, was to seize a nearby villa and the Wurzburg, while the third, led by Lieutenant John Timothy, was to act as a rearguard and reserve ...

"Straight and narrow is the path."

Last edit: 5 years 4 months ago by snowman.

The following user(s) said Thank You: Nikita, Maki, Sasha, WANGER

Please Log in or Create an account to join the conversation.

- snowman

-

- Offline

- Your most dear friend.

4 years 7 months ago - 4 years 7 months ago #4

by snowman

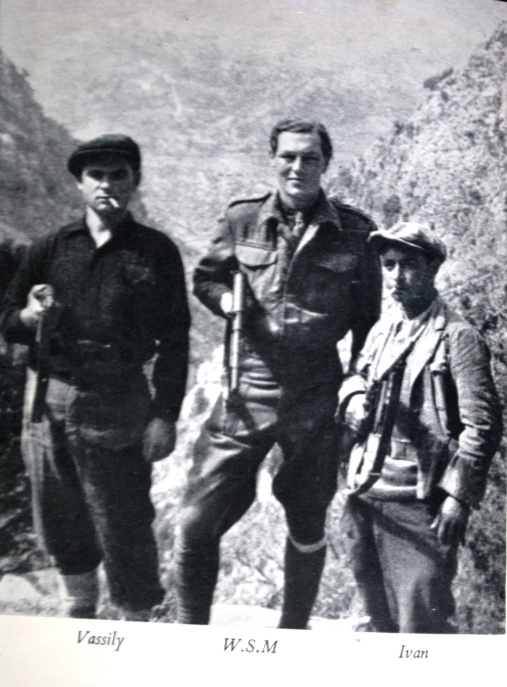

Known as Paddy Fermor, was a British author, scholar, soldier and polyglot who played a prominent role behind the lines in the Cretan resistance during the Second World War. A BBC journalist once described him as "a cross between Indiana Jones, James Bond and Graham Greene".

Due to his knowledge of modern Greek, he was commissioned in the General List in August 1940 and became a liaison officer in Albania. He fought in Crete and mainland Greece. During the German occupation, he returned to Crete three times, once by parachute, and was one of a small number of Special Operations Executive (SOE) officers posted to organise the island's resistance to the occupation. Disguised as a shepherd and nicknamed Michalis or Filedem, he lived for over two years in the mountains.

On the night of 26 April 1944, alongside his colleague William Stanley ‘Billy’ Moss and other members of the resistance, they kidnapped Major General Heinrich Kreipe, then drove him through 22 German checkpoints in his own car before abandoning it and disappearing into the mountains. After being pursued across Crete by German forces, they were finally picked upon the south coast and taken by boat to Egypt. Leigh Femor and Moss were decorated for their daring and bravery and both became famous authors after the war.

Paddy was widely regarded as Britain's greatest living travel writer during his lifetime. Moss featured the events of the Cretan capture in his book "Ill Met by Moonlight( 1957)". During periods of leave, Leigh Fermor spent time at Tara, a villa in Cairo rented by Moss, where the "rowdy household" of SOE officers was presided over by Countess Zofia (Sophie) Tarnowska.

Leigh Fermor was noted for his strong physical constitution, even though he smoked 80 to 100 cigarettes a day. Although in his last years he suffered from tunnel vision and wore hearing aids, he remained physically fit up to his death and dined at table on the last evening of his life.

For the last few months of his life Leigh Fermor suffered from a cancerous tumour, and in early June 2011 he underwent a tracheotomy in Greece. As death was close, according to local Greek friends, he expressed a wish to visit England to say good-bye to his friends, and then return to die in Kardamyli, though it is also stated that he actually wished to die in England and be buried next to his wife.

Leigh Fermor died in England, aged 96, on 10 June 2011, the day after his return.

Harry Rée was born in England in 1914. After studying at the Institute of Education, University of London (1936-37) he became a language master at Bradford Grammar School.

Harry joined the Special Operations Executive in 1940, becoming a captain serving with the Intelligence Corps. Given the code name "César" he was sent to occupied France in April 1943 as part of the Acrobat Network. Later he became head of the Stockbroker Network that was active around Belfort.

He believed that bombing of France by the RAF was counter-productive and argued that if agents were to organize the sabotage of selected factories then the German war effort would still be undermined but with fewer civilian casualties. Rée had been impressed by the destruction of the locomotive works at Fives by Michael Trotobas. During the operation four million litres of oil were destroyed and twenty-two transformers damaged and the works were out of action for two months.

To emphasize the point he orchestrated the successful destruction of the Peugeot factory at Sochaux. Later, during an attempt to evade capture, he was shot four times but still managed to swim across a river and crawl through a forest, eventually getting back to England via Switzerland.This woollen jumper shows where a bullet hole has torn the fabric – and has been darned.

The Germans became aware of his activities and attempted to arrest him. Despite being shot four times in the lung, arm, shoulder and side Rée managed to escape by swimming across a river and crawling four miles through a forest. Rée eventually got back to England via Switzerland.

After the war Rée was appointed headmaster of Watford Grammar School. He later became professor of education at York University (1961-74) where he became one of the country's leading advocates of comprehensive education and was active in the Society for the Promotion of Educational Reform. In 1974 he left York University to return to classroom teaching in Woodberry Down Comprehensive School, London, until his retirement in 1980. In the 1980s Rée continued to campaign on educational issues. This included closer links between schools in the European Community and the repeal of the 1988 Education Act. Harry Rée died in 1991.

"Straight and narrow is the path."

Replied by snowman on topic Special Operations

Patrick Leigh Fermor

(11 February 1915 – 10 June 2011)

(11 February 1915 – 10 June 2011)

Known as Paddy Fermor, was a British author, scholar, soldier and polyglot who played a prominent role behind the lines in the Cretan resistance during the Second World War. A BBC journalist once described him as "a cross between Indiana Jones, James Bond and Graham Greene".

Due to his knowledge of modern Greek, he was commissioned in the General List in August 1940 and became a liaison officer in Albania. He fought in Crete and mainland Greece. During the German occupation, he returned to Crete three times, once by parachute, and was one of a small number of Special Operations Executive (SOE) officers posted to organise the island's resistance to the occupation. Disguised as a shepherd and nicknamed Michalis or Filedem, he lived for over two years in the mountains.

On the night of 26 April 1944, alongside his colleague William Stanley ‘Billy’ Moss and other members of the resistance, they kidnapped Major General Heinrich Kreipe, then drove him through 22 German checkpoints in his own car before abandoning it and disappearing into the mountains. After being pursued across Crete by German forces, they were finally picked upon the south coast and taken by boat to Egypt. Leigh Femor and Moss were decorated for their daring and bravery and both became famous authors after the war.

Paddy was widely regarded as Britain's greatest living travel writer during his lifetime. Moss featured the events of the Cretan capture in his book "Ill Met by Moonlight( 1957)". During periods of leave, Leigh Fermor spent time at Tara, a villa in Cairo rented by Moss, where the "rowdy household" of SOE officers was presided over by Countess Zofia (Sophie) Tarnowska.

Leigh Fermor was noted for his strong physical constitution, even though he smoked 80 to 100 cigarettes a day. Although in his last years he suffered from tunnel vision and wore hearing aids, he remained physically fit up to his death and dined at table on the last evening of his life.

For the last few months of his life Leigh Fermor suffered from a cancerous tumour, and in early June 2011 he underwent a tracheotomy in Greece. As death was close, according to local Greek friends, he expressed a wish to visit England to say good-bye to his friends, and then return to die in Kardamyli, though it is also stated that he actually wished to die in England and be buried next to his wife.

Leigh Fermor died in England, aged 96, on 10 June 2011, the day after his return.

Harry Alfred Rée

(15 October 1914 – 17 May 1991)

(15 October 1914 – 17 May 1991)

Harry Rée was born in England in 1914. After studying at the Institute of Education, University of London (1936-37) he became a language master at Bradford Grammar School.

Harry joined the Special Operations Executive in 1940, becoming a captain serving with the Intelligence Corps. Given the code name "César" he was sent to occupied France in April 1943 as part of the Acrobat Network. Later he became head of the Stockbroker Network that was active around Belfort.

He believed that bombing of France by the RAF was counter-productive and argued that if agents were to organize the sabotage of selected factories then the German war effort would still be undermined but with fewer civilian casualties. Rée had been impressed by the destruction of the locomotive works at Fives by Michael Trotobas. During the operation four million litres of oil were destroyed and twenty-two transformers damaged and the works were out of action for two months.

To emphasize the point he orchestrated the successful destruction of the Peugeot factory at Sochaux. Later, during an attempt to evade capture, he was shot four times but still managed to swim across a river and crawl through a forest, eventually getting back to England via Switzerland.This woollen jumper shows where a bullet hole has torn the fabric – and has been darned.

The Germans became aware of his activities and attempted to arrest him. Despite being shot four times in the lung, arm, shoulder and side Rée managed to escape by swimming across a river and crawling four miles through a forest. Rée eventually got back to England via Switzerland.

After the war Rée was appointed headmaster of Watford Grammar School. He later became professor of education at York University (1961-74) where he became one of the country's leading advocates of comprehensive education and was active in the Society for the Promotion of Educational Reform. In 1974 he left York University to return to classroom teaching in Woodberry Down Comprehensive School, London, until his retirement in 1980. In the 1980s Rée continued to campaign on educational issues. This included closer links between schools in the European Community and the repeal of the 1988 Education Act. Harry Rée died in 1991.

"Straight and narrow is the path."

Last edit: 4 years 7 months ago by snowman.

The following user(s) said Thank You: Juanma66, Maki, Sasha

Please Log in or Create an account to join the conversation.

- Sasha

-

- Offline

- To triumphed over evil, you need only one thing - to good people inaction.

Less

More

- Posts: 512

- Thank you received: 792

1 year 4 months ago - 1 year 4 months ago #5

by Sasha

Replied by Sasha on topic Special Operations

End war by Christmas - 80th anniversary of failure Market Garden operation:

Prehistory:

80 years ago, the largest ever combined airborne operation in the history of warfare took place, the purpose of the operation was to capture the bridges over the Meuse, Waal and Rhine rivers in Netherlands and Belgium.

There were several reasons for carrying out this operation, first of all, it was the rapid advance of the Allied forces in Europe, on August 19 Paris was liberated, and on August 24 the German 5th and 7th armies were defeated in the Falaise Cauldron, large Allied forces were advancing towards the borders of Hitler's Germany, but here the allies faced a serious problem - Siegfried's defensive line, which seemed impenetrable to the allies.

Operation planning:

Field Marshal Montgomery proposed to bypass the "Siegfried Line" from the north and strike through the Netherlands in the direction of the Seider See Bay.

The plan was to throw a powerful landing force behind the Germans, which would take control of the main bridges, which would then allow the main forces of the invasion from the Netherlands into Germany to pass. The meaning of the operation did not set a long-term defense. They had to hold on to their resources from 6 to 24 hours, and tank motorized units had to approach them.

The operation plan provided for the participation of the elite 101st, 82nd Airborne Divisions of the USA, 1 Airborne Division of Great Britain and 1 Polish Airborne Brigade, which were to land with the help of parachutes and gliders, they were to be supported from the ground by 3 ground divisions.

The course of the operation:

On September 17, 1944, 1,500 planes took off from 24 English airports. There were more than 20 paratroopers in each. Some of the Douglas C-47 Dakota aircraft carried gliders, which mainly carried heavier equipment. On the other side of the English Channel, the tankers of the 30th Armored Corps of the Allies were preparing for the start of the offensive.

Paratroops drop from Dakota aircraft over the outskirts of Arnhem, 17 September 1944.

The Allies expected German resistance, but no one thought it would be so strong. No matter how perfect the operation plan is, its implementation almost always depends on additional factors.

The consequences of the miscalculations with the German forces in the area of the landing were only the beginning, which affected the further course of events. There was not enough firepower to fight tanks.

The paratroopers of the 1st Airborne Division of Great Britain landed west of Arnhem, more than 10 kilometers from the main objective of the operation - the Arnhem Bridge over the Rhine, but soon things did not go according to plan, there were more German troops in the area than expected, and the main part The 1st Parachute Brigade was quickly cut off from Arnhem.

Only the 2nd Battalion, under Lt. Col. John Frost, had reached Arnhem Bridge itself and were now in defensive positions around its northern end.

Enemy forces controlled the southern sector, and numerous improvised German units (Kampfgruppen) were thrown into action to contain the British forces.

Despite the arrival of the rest of the 1st Airborne Division for a landing west of Arnhem, no further advance was made to the combat 2nd Battalion.

To make matters worse, many British radios not worked, and the commander of the 1st Airborne Division, Major General Robert "Roy" Urquhart, was away from his headquarters and unable to direct the battle at Arnhem for some time.

The ground part of the operation was intended to quickly connect with the landing forces, this offensive was led by the Guards Tank Division with the support of two infantry divisions, despite powerful artillery and air support, the advanced units encountered stiff resistance, breaking through the enemy's first line of defense.

In the first minutes of the offensive, nine British tanks were hit by German infantry equipped with Panzerfaust hand-held anti-tank weapons.

A Sherman Firefly tank of the Irish Guards Group advances past Sherman tanks knocked out earlier during Operation 'Market-Garden', 17 September 1944.

By the end of the first day, the Guards Armored Division had reached Valkenswaard, south of Eindhoven, as planned. Further north, the US 101st Airborne Division secured most of its objectives, but was unable to stop the Germans, who had destroyed an important bridge across the Wilhelminian Canal in the Son.

Counterattack by German forces:

On the very first day of landing, the Germans found a tablet with a detailed description of the Market Garden plan in one of the broken gliders. There was no question of any element of surprise.

On the morning of September 18, the Germans attacked from the south the 2nd Parachute Battalion in its positions near the northern end of the Arnhem bridge.

Armored vehicles and semi-tracked armored personnel carriers of the reconnaissance battalion of the 9th SS Panzer Division rushed to break through the bridge, but were stopped by a barrage of shots, grenades and PIAT anti-tank grenade launchers.

Aerial view of the bridge over the Neder Rijn, Arnhem; British troops and armoured vehicles are visible at the north end of the bridge.

Despite this initial success for the Allied forces, Colonel Frost's men found themselves in a precarious position. They had only limited supplies of water, rations and ammunition, and German reinforcements were marching towards Arnhem with tanks and self-propelled guns.

Over the next two days, German counterattacks systematically broke through British positions.

On September 19, despite the Allied efforts, the most important bridge in Nijmegen was still in German hands. In desperation, Brigadier General James Gavin, commanding the 82nd Airborne Division, ordered his men to storm across the Waal River in an attempt to outflank the German defenders.

But the boats needed for this were behind the Allied column and took time to arrive.

Meanwhile, at Arnhem, four battalions of the British 1st Airborne Division made a last-ditch effort to break through to the bridge from the west, these attacks failing in the face of heavy enemy resistance. Colonel Frost's 2nd Battalion would have to hold its own.

Bad weather in Great Britain prevented the Polish brigade from arriving as planned, and the Allied landings on which the 1st Airborne Division depended were now landing on ground retaken from the Germans.

German attacks on the road between Eindhoven and Nijmegen, now known by the Americans as the "Hell's Highway", seriously hampered the Allied advance, which was now losing steam.

Nijmegen and Grave 17 - 20 September 1944: Vehicles of the Guards Armoured Division of the British XXX Corps passing through Grave having linked up with 82nd (US) Airborne Division.

German resistance everywhere increased, and the flanking operations of the VIII and XII Corps in support of the main thrust of the XXX Corps were very slow. The situation was not helped by unfavorable weather, which led to the limitation of air support of the Allies.

On 20 September, General Urquhart, now reunited with his men, ordered the remnants of the 1st Airborne Division to form a defensive pocket around the village of Oosterbeek, west of Arnhem, with a base on the Lower Rhine.

'Gallipoli II', a 6-pdr anti-tank gun of No. 26 Anti-Tank Platoon, 1st Border Regiment, 1st Airborne Division, in action in Oosterbeek, 20 September 1944.

Here they fought fierce battles against Kampfgruppe "fon Tettau", the 9th SS Panzer Division and other German units.

German tanks and heavy artillery systematically knocked them out of the buildings they were defending. That evening the armistice allowed the Germans to evacuate many of the wounded British. For those still holding out, their only hope now was that the XXX Corps would finally break through.

On September 21, the Allies captured Nejmagen, the city was now in their hands, and XXX Corps advanced to Elst, south of Arnhem.

Here he was blocked by Kampfgruppe 'Knaust'. Without support, the British tanks could not advance further along the open highway.

After radio communications were restored, XXX Corps artillery was able to provide much-needed fire support to the 1st Airborne Division, which was trapped at Oosterbeek, but little could be done to help the 2nd Parachute Battalion at Arnhem.

Cromwell tanks of 2nd Welsh Guards crossing the bridge at Nijmegen, 21 September 1944.

The bridge was now in German hands, and British resistance in the city had finally died down. In the evening the weather improved so much that the 1st Polish Parachute Brigade was finally able to land, but the result was a disaster.

Many aircraft were forced to turn back or were shot down by Luftwaffe fighters and anti-aircraft fire. Major General Stanisław Sosabowski and about 750 surviving Polish troops landed under deadly fire at Drill, from where they planned to reinforce the British perimeter near Oosterbeek.

On 22 September, after a slow advance, the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division finally reached Drill and linked up with the 1st Airborne, but it was now an evacuation rather than a reinforcement.

Allied evacuation and operation results:

On September 24-25, about 2,100 soldiers of the 1st Airborne Division were ferried back across the Rhine. Another 7,500 died or became prisoners of war.

The crossing of the Rhine and the capture of the industrial center of Germany were delayed by six months.

The operation was very ambitious and ultimately failed due to weather conditions and strong German resistance, especially near Arnhem.

But there were more reasons for the failure: the landing zones were located too far from the Nijmegen and Arnhem bridges, combined with communication problems, the difficult advance of the ground forces and several mistakes by the high command in the last days of the operation, they ultimately led to failure.

After the successful battle of Nijmegen, the Allies failed to take the last bridge in Arnhem: this whole situation is described by the famous phrase: "Bridge is too far."

Links for articles. https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/market-garden https://www.liberationroute.com/stories/184/operation-market-garden https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/the-story-of-operation-market-garden-in-photos

Prehistory:

80 years ago, the largest ever combined airborne operation in the history of warfare took place, the purpose of the operation was to capture the bridges over the Meuse, Waal and Rhine rivers in Netherlands and Belgium.

There were several reasons for carrying out this operation, first of all, it was the rapid advance of the Allied forces in Europe, on August 19 Paris was liberated, and on August 24 the German 5th and 7th armies were defeated in the Falaise Cauldron, large Allied forces were advancing towards the borders of Hitler's Germany, but here the allies faced a serious problem - Siegfried's defensive line, which seemed impenetrable to the allies.

Operation planning:

Field Marshal Montgomery proposed to bypass the "Siegfried Line" from the north and strike through the Netherlands in the direction of the Seider See Bay.

The plan was to throw a powerful landing force behind the Germans, which would take control of the main bridges, which would then allow the main forces of the invasion from the Netherlands into Germany to pass. The meaning of the operation did not set a long-term defense. They had to hold on to their resources from 6 to 24 hours, and tank motorized units had to approach them.

The operation plan provided for the participation of the elite 101st, 82nd Airborne Divisions of the USA, 1 Airborne Division of Great Britain and 1 Polish Airborne Brigade, which were to land with the help of parachutes and gliders, they were to be supported from the ground by 3 ground divisions.

The course of the operation:

On September 17, 1944, 1,500 planes took off from 24 English airports. There were more than 20 paratroopers in each. Some of the Douglas C-47 Dakota aircraft carried gliders, which mainly carried heavier equipment. On the other side of the English Channel, the tankers of the 30th Armored Corps of the Allies were preparing for the start of the offensive.

Paratroops drop from Dakota aircraft over the outskirts of Arnhem, 17 September 1944.

The Allies expected German resistance, but no one thought it would be so strong. No matter how perfect the operation plan is, its implementation almost always depends on additional factors.

The consequences of the miscalculations with the German forces in the area of the landing were only the beginning, which affected the further course of events. There was not enough firepower to fight tanks.

The paratroopers of the 1st Airborne Division of Great Britain landed west of Arnhem, more than 10 kilometers from the main objective of the operation - the Arnhem Bridge over the Rhine, but soon things did not go according to plan, there were more German troops in the area than expected, and the main part The 1st Parachute Brigade was quickly cut off from Arnhem.

Only the 2nd Battalion, under Lt. Col. John Frost, had reached Arnhem Bridge itself and were now in defensive positions around its northern end.

Enemy forces controlled the southern sector, and numerous improvised German units (Kampfgruppen) were thrown into action to contain the British forces.

Despite the arrival of the rest of the 1st Airborne Division for a landing west of Arnhem, no further advance was made to the combat 2nd Battalion.

To make matters worse, many British radios not worked, and the commander of the 1st Airborne Division, Major General Robert "Roy" Urquhart, was away from his headquarters and unable to direct the battle at Arnhem for some time.

The ground part of the operation was intended to quickly connect with the landing forces, this offensive was led by the Guards Tank Division with the support of two infantry divisions, despite powerful artillery and air support, the advanced units encountered stiff resistance, breaking through the enemy's first line of defense.

In the first minutes of the offensive, nine British tanks were hit by German infantry equipped with Panzerfaust hand-held anti-tank weapons.

A Sherman Firefly tank of the Irish Guards Group advances past Sherman tanks knocked out earlier during Operation 'Market-Garden', 17 September 1944.

By the end of the first day, the Guards Armored Division had reached Valkenswaard, south of Eindhoven, as planned. Further north, the US 101st Airborne Division secured most of its objectives, but was unable to stop the Germans, who had destroyed an important bridge across the Wilhelminian Canal in the Son.

Counterattack by German forces:

On the very first day of landing, the Germans found a tablet with a detailed description of the Market Garden plan in one of the broken gliders. There was no question of any element of surprise.

On the morning of September 18, the Germans attacked from the south the 2nd Parachute Battalion in its positions near the northern end of the Arnhem bridge.

Armored vehicles and semi-tracked armored personnel carriers of the reconnaissance battalion of the 9th SS Panzer Division rushed to break through the bridge, but were stopped by a barrage of shots, grenades and PIAT anti-tank grenade launchers.

Aerial view of the bridge over the Neder Rijn, Arnhem; British troops and armoured vehicles are visible at the north end of the bridge.

Despite this initial success for the Allied forces, Colonel Frost's men found themselves in a precarious position. They had only limited supplies of water, rations and ammunition, and German reinforcements were marching towards Arnhem with tanks and self-propelled guns.

Over the next two days, German counterattacks systematically broke through British positions.

On September 19, despite the Allied efforts, the most important bridge in Nijmegen was still in German hands. In desperation, Brigadier General James Gavin, commanding the 82nd Airborne Division, ordered his men to storm across the Waal River in an attempt to outflank the German defenders.

But the boats needed for this were behind the Allied column and took time to arrive.

Meanwhile, at Arnhem, four battalions of the British 1st Airborne Division made a last-ditch effort to break through to the bridge from the west, these attacks failing in the face of heavy enemy resistance. Colonel Frost's 2nd Battalion would have to hold its own.

Bad weather in Great Britain prevented the Polish brigade from arriving as planned, and the Allied landings on which the 1st Airborne Division depended were now landing on ground retaken from the Germans.

German attacks on the road between Eindhoven and Nijmegen, now known by the Americans as the "Hell's Highway", seriously hampered the Allied advance, which was now losing steam.

Nijmegen and Grave 17 - 20 September 1944: Vehicles of the Guards Armoured Division of the British XXX Corps passing through Grave having linked up with 82nd (US) Airborne Division.

German resistance everywhere increased, and the flanking operations of the VIII and XII Corps in support of the main thrust of the XXX Corps were very slow. The situation was not helped by unfavorable weather, which led to the limitation of air support of the Allies.

On 20 September, General Urquhart, now reunited with his men, ordered the remnants of the 1st Airborne Division to form a defensive pocket around the village of Oosterbeek, west of Arnhem, with a base on the Lower Rhine.

'Gallipoli II', a 6-pdr anti-tank gun of No. 26 Anti-Tank Platoon, 1st Border Regiment, 1st Airborne Division, in action in Oosterbeek, 20 September 1944.

Here they fought fierce battles against Kampfgruppe "fon Tettau", the 9th SS Panzer Division and other German units.

German tanks and heavy artillery systematically knocked them out of the buildings they were defending. That evening the armistice allowed the Germans to evacuate many of the wounded British. For those still holding out, their only hope now was that the XXX Corps would finally break through.

On September 21, the Allies captured Nejmagen, the city was now in their hands, and XXX Corps advanced to Elst, south of Arnhem.

Here he was blocked by Kampfgruppe 'Knaust'. Without support, the British tanks could not advance further along the open highway.

After radio communications were restored, XXX Corps artillery was able to provide much-needed fire support to the 1st Airborne Division, which was trapped at Oosterbeek, but little could be done to help the 2nd Parachute Battalion at Arnhem.

Cromwell tanks of 2nd Welsh Guards crossing the bridge at Nijmegen, 21 September 1944.

The bridge was now in German hands, and British resistance in the city had finally died down. In the evening the weather improved so much that the 1st Polish Parachute Brigade was finally able to land, but the result was a disaster.

Many aircraft were forced to turn back or were shot down by Luftwaffe fighters and anti-aircraft fire. Major General Stanisław Sosabowski and about 750 surviving Polish troops landed under deadly fire at Drill, from where they planned to reinforce the British perimeter near Oosterbeek.

On 22 September, after a slow advance, the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division finally reached Drill and linked up with the 1st Airborne, but it was now an evacuation rather than a reinforcement.

Allied evacuation and operation results:

On September 24-25, about 2,100 soldiers of the 1st Airborne Division were ferried back across the Rhine. Another 7,500 died or became prisoners of war.

The crossing of the Rhine and the capture of the industrial center of Germany were delayed by six months.

The operation was very ambitious and ultimately failed due to weather conditions and strong German resistance, especially near Arnhem.

But there were more reasons for the failure: the landing zones were located too far from the Nijmegen and Arnhem bridges, combined with communication problems, the difficult advance of the ground forces and several mistakes by the high command in the last days of the operation, they ultimately led to failure.

After the successful battle of Nijmegen, the Allies failed to take the last bridge in Arnhem: this whole situation is described by the famous phrase: "Bridge is too far."

Links for articles. https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/market-garden https://www.liberationroute.com/stories/184/operation-market-garden https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/the-story-of-operation-market-garden-in-photos

Last edit: 1 year 4 months ago by Sasha.

The following user(s) said Thank You: snowman

Please Log in or Create an account to join the conversation.

Birthdays

- Ikaros in 3 days

- jamaicadomnului in 3 days

- Stonewall in 6 days